Recently I got a chance to attend RIMEX 2018 in Oaxaca de Juárez, Oaxaca, the annual national conference for Rotarians from all over Mexico. Oaxaca is known for being Mexico’s “most indigenous state,” made up of 16 different indigenous ethnic groups with over a million speakers of various native languages. Unfortunately, it is also known for being one of the poorest states in Mexico. However, it is so much more than that. The days I spent in Oaxaca for this conference were some of the most enjoyable I have spent in Mexico so far. I truly cannot describe the joy that getting to know the beautiful and diverse places and people of this country, the homeland of my family, gives me. Es más, that joy is not static… my Oaxaca trip made me realize that it grows exponentially with each new place and each new face. So here I seek to share the simplest and purest moments of my happiness with all of you 🙂

When you find yourself.

When you find yourself.

Where.

your breath is happy.

you feel free.

Y encuentras tu canto.

que te das cuenta tu sangre nunca se lo olvidó.

This is Home.

Machismo

Most of the time they feel distant.

The headlines that I read from the US.

Like part of a past life of mine.

Like the hundreds of miles between me and the horrible events they talk about separate me from their impact.

But these.

These are different.

The headlines that speak of Reduction.

Reduced… presence.

Reduced… voice.

Reduced… to how well she fits beauty standards created by and for men.

Reduced… respect. everywhere. always.

Reduced… safety when walking around by herself.

Reduced… power during sexual encounters.

Reduced… credibility when she speaks her truth.

(especially if it threatens the reputation or power of a man.)

Reduced… chances of justice when she is wronged.

Reduced… life chances.

These reductions know my name.

That is why the stories coming out recently do not feel distant.

In fact, they feel too close to me here in Mexico.

Uncomfortably so.

They strike me in a place that I can’t deny or ignore.

They strike me.

Every time I pass a man in this city and feel his gaze move up and down my body.

evaluating me.

They strike me.

Every time a new male “friend” of mine assumes my common friendliness means I am “interested.”

and then gets angry with me when I tell him I’m not.

They strike me.

Every time a taxi driver inappropriately asks me questions about my love/sex life.

without even knowing me.

They strike me.

Every time a man does not respect my “no.”

in any situation, intimate or otherwise.

They strike me.

No matter where I am in the world,

I feel reduced.

I feel violated.

Es decir, I feel what it means to be a woman.

Hay que ver más allá de mirar

“¡Mira por aquí!” (“Look over here!”) shouted about 5 Rotarians as they waved their hands and snapped several pictures in rapid succession of a pregnant woman receiving her care package, face dazed, from a young Rotary exchange student, a well-practiced smile plastered to her face.

That exchange student was me.

These moments—which happened each time I, or another member of our team, handed one of our care packages to a local community member—are what stood out to me the most during my first trip to deliver aid to a rural Chiapas community affected by Mexico’s September 7th earthquake. As somewhat of a rookie at this kind of event, upon arriving to the community, I just kind of followed the instructions of the Rotarian leading the trip about where to be and what to do. It wasn’t until I had started unloading the large plastic bags of food, diapers, and other basic necessities from the trucks and handing them to their intended recipients that I realized that the Rotarians on our team were arranging everyone according to what would look best for the photos. In fact, everything about the trip – from which persons from our team were handing out packages to which spot we were standing in when handing them out to which sites we went to see in the community – seemed to be controlled by what would look best for photos like the ones below.

This reality made me not only very uncomfortable as I handed out packages, but also consumed my thoughts to the point that I was silently fuming.

Why?

This reality reminded me of the type of “philanthropy” that is designed for photos. The type that’s designed to be seen (and praised) by others. The type that centers the “do-gooder” and whose primary purpose is to enhance the social/moral reputation of that person.

More specifically, to me, this reality reminded me of voluntourism, in which white(r), Western actors take pictures of members of marginalized communities (usually persons of color from non-Western cultures) without their consent and proceed to post them on social media, flaunt them around as evidence of their “good deeds,” or use them for other selfish purposes. This practice objectifies the people in the photos since they are treated as props (often exoticized and/or victimized) for the objectives of the photographer(s), who don’t even consider that these community members may not want to be photographed in the first place and who often never facilitate community members’ access to these photos of themselves after they are taken.

All these thoughts passed through my head as I watched members of our team take every person’s photo without asking a single one of them if it was okay. However, I didn’t know whether to say something to protest or not because, again, this was my first time participating in this kind of event, and I wasn’t 100% sure if these photos had a purpose other than the one I suspected: PR (public relations) campaigns for Rotary. So I stayed silent. Silent and uncomfortable and angry.

I eventually stopped smiling for the pictures and just tried to concentrate on what I was doing, while at the same time making a point to observe the local community members and their reactions to all the photos we were taking.

I noticed that whether it was an old man, a middle-aged woman or an adolescent, the majority of the community members did not smile when their photo was taken. Most people’s faces were confused or indifferent, with several looking off into the distance when we took the photo instead of looking at the camera.

This only deepened my anger, but still, aside from making faces of disdain at my roommate Ceci every time the Rotarians made a big show about the pictures, I did nothing. And I felt guilty – or at least conflicted – about my decision. Should I have said something? Should I have called out my fellow team members (in a respectful way of course) for their seemingly shallow prioritization of potential PR opportunities for Rotary over respecting the human dignity of the community members in front of them?

At the end of the distributions, everyone was obliged to be in the large group photos with our team members who participated in the event and the community members who had received aid.

I briefly mentioned something to Ceci after the event about the exaggerated emphasis on photographs, but she did not seem as concerned as I was, so I thought she had simply become accustomed to the reality like the rest of our Rotarian team had seemed to be.

However, a week later, I overheard a conversation between two Rotarians talking about the corruption that exists among some organizations coordinating aid for the earthquake victims in Mexico. Often, the families most in need do not receive anything because the goods are stolen by those who do not need them or are hoarded by a small number of families in need. They were talking about how paper documents that keep track of exactly who received what can easily be falsified, and so Rotary concluded that the only way to prove that a certain family or individual received his or her care package was to take pictures of every single person receiving the physical package.

I was shocked – less by the actual reason behind what I had observed during the aid distribution and more by the fact that I hadn’t thought about that possibility.

And suddenly I realized that I had completely misconceptualized Rotarians’ emphasis on taking good, clear photos during the distribution of packages. Of course, they could have warned the community members beforehand that photographs were going to be taken of them and their children, while explaining why taking a photo of each person was so important (instead of just imposing it on them without asking), but I actually am glad they were so thorough. This way, Rotary has evidence that they provide the community aid they say they do and donors continue to trust that their donations are not going into Rotarians’ pockets. Rotary is truly an impressive organization in terms of the geographical breadth and diversity of its capacities when it comes to providing aid in a humanitarian crisis, and it is well suited to help the dozens of small, rural communities affected by the September 7th earthquake in Chiapas. This is one the many reasons I am glad I misperceived the situation when I was in that rural community helping to deliver aid. I am even more relieved that I didn’t say anything at the time based on my initial assumptions.

As a student of anthropology, I am trained to be wary of my own assumptions and to analyze how they affect the way I operate in my environment. In this case, I am glad I listened to my initial hesitation to act on my negative assumptions about why the Rotarians wanted to take so many pictures. As someone who identifies as a social justice advocate, I am always ready to call out or rectify situations of injustice that I encounter in my daily life. However, this experience was an important reminder that sometimes, especially when I am in unfamiliar contexts like that of another country for example, I should investigate further before passing judgment on a situation of apparent injustice, because I may be looking (“mirar” in Spanish) but not truly seeing (i.e. understanding; “ver” in Spanish) what is happening in front of me.

A picture of our team:

On the other side

Since it has been a while since my last post, this one will be just a general update about my life.

My biggest update explains my long absence. In short, basically every time I go abroad I have some sort of health crisis (because I’m an old woman with chronic health problems to begin with, so of course). I am hoping what just happened to me counts as mine for Mexico.

About three weeks ago today, I ate a very mediocre dinner at a bar with live music, and I am absolutely convinced the food was contaminated by someone who did not wash their hands. At first I thought it was my lactose intolerance and IBS acting up, but after spending the entire first night tossing and turning with severe abdominal cramping, I realized it was something more serious. Skipping over the intimate details, I essentially came down with a severe intestinal infection that took me three doctor’s visits, a hospital stay, and two weeks of eating small amounts of bland, fat-less food to recover from. Despite conducting all types of laboratory tests on me, apparently the doctors could not specify exactly which bacteria I had, but they think it was probably E. Coli. In fact, I am still not 100% better since I am still taking medicines for some remaining symptoms, but I am definitely grateful to at least be eating normally again and be participating in my normal activities.

Maybe I am being dramatic, but this illness experience was actually kind of profound. I learned two big things about myself that I didn’t know before I got sick:

1. I realized just how much joy food brings me in my life.

2. I realized that I would be miserable as a “vegetable” as they say. Two weeks being bedridden and then being too weak to go out of the house much felt like years of torture to me… especially during this festive season of Christmas celebrations. I realized that I would want to be “unplugged” if there was no hope of my state changing. Although morbid, I am actually kind of excited that I now know this about myself because before my illness, I had always thought about it and had no idea what I would want.

In other news, Feliz (belated) Navidad! I am proud to say that I officially spent my first Christmas away from home. While it was weird to not be with my family for the holidays and I did have some FOMO when I facetimed them on Christmas Eve, overall I am really glad I decided to stay here in Chiapas for the holiday season.

I was able to attend the celebration of la Virgen de Guadalupe on the 12th of December and during the days leading up to it. This día feriado (holiday) is a very special and unique part of the Christmas season here in Mexico. Groups of people from all over the country make pilgrimages, taking turns running (yes literally running – sometimes for days) to a church dedicated to Our Lady of Guadalupe. For a whole week prior to the 12th, groups poured into San Cristóbal bearing Our Lady’s image—often bathed in flowers, on a pedestal, and/or accompanied by a band—as well as a torch lighted for this very purpose, to leave them with the main statue of Our Lady at the church. It was a beautiful procession to watch and I imagine an amazing and difficult spiritual journey for those participating. If I wasn’t such a grandma, I would want to do it myself.

I also knocked participating in a traditional posada off my bucket list. I was one of the few people there who was not a child or the mother of a child (they were there mostly for the candy), but I thoroughly enjoyed processing through a local neighborhood in a recreation of Mary and Joseph’s journey looking for shelter for the birth of baby Jesus.

Finally, I got to celebrate Christmas Eve with my “aunt” and “uncle” (really distant relatives of mine that live in San Cristóbal), their extended family, and a friend who would have been alone for Christmas if I hadn’t invited him to spend it with us.

My illness and the holiday season have helped me to realize just how strong of a community I have built here in San Cristóbal. I realized I truly do have a “Mexican family” and several good friends who really care about me and who have significantly enriched my experience here in Chiapas. It is amazing to me that I am able to say that just a month after I posted about struggling with loneliness here. However, in less than a month even participants in my research study have become really good friends of mine, and for that, I cannot thank God enough.

Honestly, I am really happy here in San Cristóbal, and I can’t believe my stay is almost halfway through! I hope to live up my time here even more as I start my final class in January and begin to analyze my research data. Much love and holiday spirit from “La Tierra Mágica” (The Land of Magic) to all of you wherever you are in the world. Que Dios los bendiga.

I’m not immune

I think it took me a while to recognize because I’m not used to it.

The truth is I never associated it with myself.

I think I subconsciously thought I was immune to it.

“It.”

The feeling that has been in the background of my mind and heart ever since the shiny newness of my life here in San Cristóbal had begun to wear off.

“It.”

Loneliness.

I never thought that I, an extreme extrovert, would be feeling this. I mean, I make friends so easily! Or at least that’s what everybody tells me. Not only that, I make friends with all different types of people! No matter where I am! I have always been able to do that without thinking about it… So how did I end up here?

Sure, my friends who had moved to a new place to continue their studies or to work at a new job were feeling this. And it made sense when they told me about it. I mean they had just graduated from college and had moved to huge cities like New York or LA where they didn’t know anyone. But I never considered that it could, or would, happen to me… especially in a culture that I love, while I am studying the things that I love, and while I am surrounded by lots of other young people. I mean adaptability is one of my greatest strengths! I am the person that never gets homesick no matter where I am. So of course I didn’t have to worry about becoming lonely…

Pretty silly of me, huh?

Because, all of a sudden, I realize that I do feel lonely. This may be surprising since in my first blog post I said that I felt like I was already beginning to build a community here in San Cristóbal, which was true at the time. But the reality is that that initial feeling of warm embrace has since dwindled since I settled into my normal routine here in the city. This is not because my hosts have stopped being welcoming and friendly towards me. Rather, I think it has more to do with the fact that the people who embraced me initially were 10+ years older than me, meaning they had jobs, kids, and/or other obligations that took up a lot of their time. During my first couple weeks here, I know they made the extra effort to make me feel welcome by organizing events and inviting me to do things with them to help me get to know the city and adjust to my new life here. However, that schedule was just not sustainable for them, and so with time, we all settled into our normal routines, with theirs including time with their “normal” group of friends, and mine lacking in that department.

I understood that and actually expected this shift to come after my first couple weeks here to be honest. I just thought I would have started to make new friends on my own by that time.

But honestly how does one make friends?

The combined experiences of my friends and I tell me that it’s actually pretty hard as a young adult.

I can’t exactly scope out random strangers who look my age, choose one that looks nice, and then go up to him or her and ask “Will you be my friend?” like I did in 2nd grade.

But I wasn’t too worried about it before arriving to Mexico, specifically because one of the benefits I saw to enrolling in local universities was that it give me an easy way to make friends with people similar to me in age and life stage and allow me to integrate myself more easily into the local culture/community. However, upon starting classes at EcoSur I quickly realized that this ideal scenario of mine was not going to happen. For one thing, I found myself with only 3-5 other students at a time, so my options were pretty limited when it came to finding someone with whom I “clicked” enough to want to become friends. All my classmates were very nice, but you can say that I never really “hit it off” with anyone. Secondly, my peers commuted to and from school, so they often left right after class, leaving little time for us to casually chat or learn about each other’s lives. Thirdly, several of my classmates were significantly older than me and/or already had children of their own to take care of, so it was clear that we were in different stages of life, which made connecting as friends to hang out, go explore, go to cultural events with, etc. a bit more difficult.

Since my original plan didn’t work out as expected, I turned to the next most obvious source of friends: my servers at restaurants of course (hahaha). No but, all joking aside, it actually wasn’t an intentional decision on my part to try to make friends in this way. Rather, often times (due to having no friends) I go out to eat by myself.

[As can be seen in the photographic evidence below, while I do eat rico (delicious food) here, a lot of times it is a party of uno (yes I am basic and take pictures of my food for Instagram – you know you do it, too).]

And well, because I am naturally friendly (and because I don’t have anyone else to talk to if I’m eating alone) I often begin casual conversations with my servers, the vast majority of whom are around my age. Over time, since I frequent the same cafés and restaurants regularly, certain servers and I have gotten to know each other pretty well to the point where I have even hung out with some of them outside of their work. However, even so, most of these people have remained to me what Mexicans call “conocidos” (people I greet and talk to when I run into them), and they have not turned into “amigos cercanos” (close friends with whom I make plans to hang out with regularly), which is what I really want.

In my latest attempt at meeting new people and making friends (while doing something I love), I began taking salsa and bachata classes at a local dance studio. However, even though the dance class is very fun and a great workout, once again my plan didn’t work out the way I thought, since there are only 3 other people taking the class with me, none of whom are my age.

I mean don’t get me wrong, my roommate/long-lost mother Ceci and I get meals and do other things together whenever she can, my “tías y tíos” (the other members of the Rotary Club who is hosting me) try to keep me informed about cultural events and/or holiday celebrations in the city so I can experience them, and I often hang out with the one good girlfriend I have made aside from my roommate. However, when they are all busy with work or their kids or when it becomes evident that they are just in a different stage of life than I am (which happens fairly often), I realize that it’s just not the same as having a core group of friends of my own peers.

As someone who gains energy from others, likes to go dancing and do other social things, and processes her thoughts and experiences through verbalizing them, I consider having several close friends to be an essential part of my day-to-day happiness. And of course being in a new country where I am having new experiences, challenges, and opportunities for adventures every day heightens my desire for this type of companionship. On top of this constant reality, Ceci has taken several recent trips for work that have left me feeling more alone than usual.

However, the point of this post is not to solicit pity or sympathy. To the contrary, something weird happened when I finally came to terms with what I was feeling. Once I put a name to my loneliness, recognized it, and owned it, I felt like I gained a certain type of peace from that knowledge. Sure, I still feel lonely, but now I feel like I understand that feeling a little bit better, and I can respond to it in a more productive way than ignoring it and sulking.

More specifically, in terms of my response to this loneliness of mine, I see an opportunity. I feel like often times as an extreme extrovert, I tend to rely too much on my interaction with other people for my own contentment on any given day. So I feel like maybe this solitude that I am experiencing right now is a chance for me to practice being “okay” with being by myself, being “okay” with being alone, and being “okay” with not being okay. I know this will be a process, and probably not the most fun one, but in the end I hope to have grown in ways I wouldn’t have otherwise surrounded by all the friends in the world. This does not mean that I am going to stop trying to make friends. But rather, it means I am not going to allow anxious addiction to social interaction to drive my friend-making attempts, nor am I going to pin my mood on a given day on the outcomes of those attempts. And in the mean time, I am going to mindfully take advantage of the extra time I have to get to know me, spend quality time with me, listen to my inner most thoughts/dreams/desires and make me happy. As an naturally empathetic extrovert, I have never been really good about self care. So maybe this is God finally forcing me to learn how to do it.

To all my fellow lonely recent college grads, I feel you. I know it’s tough, but I hope you find opportunity for your form of personal growth in this experience of solitude as well ❤

My two months como “ñoña”

I know it has been a long time since I posted, but I promise it was for a good reason… School!!! My roommate Ceci tells me that the word in Spanish commonly used for “nerd” is “ñoña/o,” so this post will basically fill you in on what exactly I have been doing/learning during the past two months as a “ñoña” in typical Briana-fashion:

For the first two months of my stay here (early September through early November) I enrolled in courses at the local university EcoSur, which is an institution that specializes in interdisciplinary studies oriented toward the development of the southern border region of Mexico (where I am) and the Caribbean. The classes at EcoSur are structured a bit differently than college classes that I am accustomed to in the U.S. Each class is a 1-month intensive course, so I can only take one class at a time.

I have participated in two of these month-long classes as part of EcoSur’s MSc program in Natural Resources and Rural Development. I specifically chose classes that would help prepare me for my research project, which is focused on the prevention of HIV/AIDS and other STIs among migrant indigenous youth, particularly young women.

First class: “Down with the patriarchy”

The first class I took was about the relationship of sexuality and reproductive health to gender and human rights. In total, we were five students and 1 professor, all female. I couldn’t help but think that it was probably not a coincidence that this course only attracted females, since our patriarchal society teaches men that they need not concern themselves with the topics of gender and reproductive health. As my first Master’s class ever, and one conducted completely in Spanish at that, I was a little nervous that it might be rather difficult. However, the small size of the class, the friendliness of my classmates, and the candid humor of the professor allowed for an intimate and non-intimidating environment for us to discuss things like:

- the historical creation of the gender/sex system under which our society operates today,

- international principles and norms of the UN and other organizations that deal with sexual and reproductive rights,

- the subordination of women and LGBTQ+ in our patriarchal society

- and the factors impeding youth’s access to contraceptives in Mexico and the implications that this situation has for health (i.e. adolescent pregnancies, transmission of sexually transmitted infections, etc.)

As a seminar, the class was structured around daily readings that we took turns presenting at the beginning of each session, which was followed by in depth-discussion of the readings. I appreciated that many of the readings assigned to us highlighted issues local to the region or at least relevant to Mexico in general, with some articles even having been written by our very own professor. This allowed me to understand the complex issues we were studying in the specific local context I am currently in and in which I plan to conduct my investigation. Furthermore, I gained many insights by being forced to widen my perspective beyond articles or publications written by American researchers. Since this was a Master’s class, I felt like our discussions were even more fruitful due to the fact that each of us had received a different undergraduate degree ranging from anthropology to psychology to medicine and so brought different perspectives to each issue. I also really enjoyed when outside professors attended our class as guest speakers and the psychology-based workshop we did aimed at helping us understand and connect more deeply to ourselves and our place in the world through art. Overall, I feel like I successfully completed my first Master’s level class, which helped me grow more than anything in reading about and discussing complex topics like gender, sexuality, and reproductive health from an academic perspective in Spanish.

Second Class: Learning the hard way

My second class was focused on gender and other inequalities in the southern border region of Mexico. Similar to the first class, we were only four students, three girls and one guy. However, this time we had three professors. Rather than meet every week day like we did in the other class, this class only met once a week because it was based on weekly projects that were carried out in a group or individually outside of class. Once a week I also met with one the professors for a personalized advising session. This course was designed to help us advance in modifying our protocols for our research projects.

Due to being project-based, this class was very time-consuming, so at first, I was annoyed by the work because I perceived the class projects as taking time away from working on my protocol (which I wanted to submit for ethical review as soon as possible). However, since the projects consisted of reviewing certain aspects of the research literature, as well as the landscape of local NGOs (non-governmental organizations) and government agencies, related to the topic of my proposed project, in reality they turned out to be useful, even if tedious. Furthermore, the personalized advising sessions and the fact that we had to present each project in class allowed me to receive feedback from my peers and professors that was also useful. Specifically, this class helped me expand my search for knowledge that already exists on my topic, encouraging me to not only find new or unconventional sources of information, but to critically analyze them and their contributions. This process helped me better understand the positioning of my study within its local and regional context, as well as define with more clarity certain aspects of my theoretical approach and methodology. In the end, I was grateful for having been in the class because it led me to develop a deeper understanding of the importance of having a historical, critical, empathetic, and holistic approach to conducting research.

Research Project: Ch-ch-ch-ch-changes

After the aforementioned classes at EcoSur and multiple meetings with my advisors from CIESAS (the anthropological research center through which my research will be conducted), I came to a very sad realization: I was not going to be able to do the project I had been planning for almost 2 years. Why? Because the project I had designed was originally meant to be conducted over a period of 9-12 months, and I only have less than 6 months (I have to present my results in early May). This situation is a result of the specific requirements of the Rotary Global Scholarship I ended up getting to come to Mexico (which required me to enroll in formal classes rather than spend all my time doing research).

To be completely honest, making these “cuts” to my project broke my heart a little, especially since I felt that some of the parts that I had to cut were particularly creative and innovative, but I knew I had to be realistic. I knew it was better to reduce the scope and aims of my project to produce meaningful results than to try to take on too much and end up producing lower quality work that is less useful for my population. Among the most important changes I made is my decision that my study will be descriptive rather than analytical. This means that I will no longer be conducting in-depth interviews or focus groups, nor will I be using photography as I had originally planned. Rather my methodology will consist mostly of participant observation, a classic anthropological technique that involves, yep, direct observation of the population of interest, as well as participation in activities with the population of interest. Another important change is that I will now be focusing specifically on university students among the population of migrant indigenous female youth in San Cristóbal.

As of now, I am anxiously waiting on the official approval of my study protocol by the ethical review committee of CIESAS for me to be able to begin my fieldwork. To be honest, I am feeling excited, but also very pressured by my time limitations, so please send good vibes that the approval comes soon!!!

Don’t know what Ayotzinapa is? You should.

I had just arrived home when all of a sudden I heard far off shouting and the sound of crowds coming from the window that got louder and louder. I immediately went to the window, knowing it was protest.

Upon walking out onto my balcony, I noticed that people filled up my street for as far as I could see, trudging through the rain while carrying signs, cardboard cut-outs of bodies, and professional banners covered with outcries of indignation, desperation, and determination (click through to the second panel on this instagram post for video footage). They chanted endlessly: “We want them alive because they were taken alive!” and “Advance the struggle of the people!”

(( Translation of phrases on the card-board cut out in the above image:

Raised right arm: “We dont forget!” “Where are we [the students]?”

Lowered left arm: “Justice”

Head and chest: “They were taken alive so we want them alive” “43”

Stomach: “It was the State[‘s fault]”

Left leg: 3 years [in reference to the anniversary]

Right leg: Ayoztinapa ))

Although this post is coming two days late, I knew I had to write about what I saw. That protest I witnessed was planned in commemoration of the 3rd anniversary (September 26th) of the tragedy perpetrated against 43 Mexican students from the Ayotzinapa Rural Teachers’ College, who were “disappeared” by a collusion of local government officials, police officers, and gang members in Iguala, Guerrero (as well as potentially other State employees at the municipal and federal level).

The story:

These students were poor, rural, activists with a thirst for knowledge and a desire for social change — aka they were a threat. That is why they were probably killed. However, their families, the rest of Mexico, and the rest of the world have still not received any definitive answers as to what exactly happened to them. Official reports from the police investigation are considered untrustworthy by independent experts and the families of the students. I don’t know everything about Ayotzinapa, but I do know that this is not an isolated case. People–ranging from activists and journalists to ordinary, innocent little kids–are disappeared all the time in Mexico. This case is simply a micro-manifestation of deepening inequalities in Mexico, the violent chaos of Mexico’s drug war, the corruption of Mexico’s political institutions and criminal justice system, and the widespread impunity that perpetrators of heinous crimes like this enjoy in Mexico.

And as U.S. citizens, we are not completely disconnected from this reality. One of the most explicit examples is the fact that the U.S. government continues to give millions of dollars every year in military and police aid to Mexico to sustain the drug war, which since 2007 has resulted in well over 100,000 murdered, 25,000 disappeared and one million displaced in Mexico. However, there are so many other ways in which we are connected to and thus complicit in the current situation in Mexico and the suffering it causes so many of its people. For that reason, we have an obligation to start paying more attention, educating ourselves, and demanding change in solidarity with our Mexican brothers and sisters.

Photo Source: Carlos Jassau/Reuters, El Universal

Without justice, there will be no peace. That is why the parents and families of the 43 disappeared students have not stopped marching, sharing their story, or using their case to shed light on the chronic abuses and injustices facing the Mexican people, since this tragedy happened.

Here in Chiapas, one of the most impoverished, rural, and unequal states in Mexico, the inflammatory case of Ayotzinapa hit home hard since Chiapanecans are no strangers to injustice. That’s why locals here in San Cristóbal regularly hold marches in protest and remembrance of the 43. That’s why outcries in the form of graffiti can be found all over the city. That’s why I have felt so connected to this case since I arrived.

Caption of second image (red poster): “They wanted to disappear us and we appeared all over the world” ; Caption of fourth image: “We are waiting for the 43” ; Caption of fifth image: “We will not forgive or forget” ; Caption of seventh image: “Ayotzinapa lives!” ; Caption of eighth image: “Justice” ; Caption of ninth image: “Peña [the current president of Mexico]: murderer”

Final thoughts:

I wanted to write this post because I feel like a lot of English-speakers do not know (enough) about Ayotzinapa, and I wanted to try to do my little tiny part to help change that.

To the 43 students, may you rest in power. As a fellow student with a fire for justice, I personally commit myself to continuing the fight that you died for.

To the families, loved ones, and community of the 43 students. I see you. I love you. I stand with you in your struggle for truth, justice, and change.

To Mexico, you are a beautiful country with a complicated history and present reality, but I know you can be so much better. I continue praying for your people, for my heart has always been inextricably connected to theirs.

Other links of interest for further reading:

Timeline of Events related to the Ayotzinapa disappearances: https://www.amnesty.org/en/latest/news/2015/09/mexico-ayotzinapa-student-s-enforced-disappearance-timeline/

Inter-American Commission on Human Rights reports related to Ayotzinapa based on investigations carried out by an Interdisciplinary Group of Independent Experts (GIEI by its initials in Spanish): http://www.oas.org/en/iachr/activities/giei.asp

Quality analysis of Ayoztinapa and its significance: http://www.drugpolicy.org/blog/ayotzinapa-vive-one-year-anniversary-students-disappearance-families-continue-demand-truth-just

Self-critique

People watching. Like I do.

Breeze flowing through the plaza.

Cooling my neck.

Cooling my café as it touches my lips.

Cooling the hot topic of our conversation: social justice.

A messy complexity

that takes the luxury of a Sunday morning brunch to unravel, unentangle.

but never completely.

— Disculpe la molestia, ¿le gustaría ver mis pulseras?” —“No, gracias” [my smile soft, my eyes taking in the woman’s traditional traje] —

my partner en pensamiento: my roommate.

why am I here in la tierra mágica?

— “Por favor, ¿alguna moneda, reina?”– “No… perdón…” [another smile… still soft, less comfortable, still genuine] —

I am here to study the health of the local indigenous peoples.

es decir, to learn

and (PERHAPS, con suerte)

To contribute to knowledge through research.

So to “help”?

A big assumption.

How to conduct a study that produces something “helpful”?

Difficult, to say the least.

— “¿Quieres un corazón tejido?”– “No, gracias” [my smile sweet as can be, because it’s a child]

“Por favorrrrrr, te lo doy por 10 pesos….”–“No, gracias” [still smiling, my voice apologetic] “Ok, 5! Te lo doy por 5!”– [hesitation]… after all, what was 5 pesos to me?… “No, perdón.” [extremely apologetic, guilt bleeding into my voice] —

Goal: To produce at least something… concrete. Tangible.

Desired by the community.

The ideas flow between us, carried by the breeze.

The challenges and importance of community-engaged research.

Made more complicated cuando hablamos de working with a marginalized group.

Like the indigenous people of Chiapas.

— “Dame ese pan por fa” and from me, a sigh of relief that this time it is my roommate who has to say,“No hija” to a child even younger than the first [more experienced than me in this situation, her tone respectful, but firm] —

talking talking talking.

About how I am so committed to “my” population

To respecting them,

their wishes,

their autonomy,

— “¿Le interesan estas blusas?”– “No, gracias” –“Mira, tengo pulseras….” — “Noo, gracias. Lo siento.” –“También tengo animales… Mira!”– “No, gracias” — “Te, te lo doy por 10 pesos….son muy bonitos.”–“Noo, gracias.” [still smiling, shaking my head, my voice apologetic] —

And I turn away from “my” population

and back to my brunch

for the twentieth time in one meal.

But this time, as I bring my capuchino to my lips

the rank smell of inequality hits my nose.

And then, upon drinking,

an unexpected aftertaste.

Much too strong.

Two flavors begin

playing around on my tongue.

One, overpowering, but familiar:

the bitter taste of privilege

(crafted only from the highest quality, organic ingredients, of course).

The second,

I can’t quite discern,

as it lingers on the edge of my palette:

…is it… a splash of… hypocrisy?

I’m not sure

because I am not accustomed to that taste.

But my stomach sinks at the thought.

And I leave the meal with an upset stomach.

[…]

A week passes.

Then, two.

as well as dozens more interrupted meals on the plaza to mull it over.

And after smelling

and tasting,

during every meal,

again and again

(because the smells and flavors never went away),

I think

my mouth was playing tricks on me.

A lo mejor, it wasn’t hypocrisy.

a lo mejor, it was a splash of humanity.

The Earthquakes in Mexico: Can Mother Nature shake us into believing in climate change?

“How obnoxious!” I thought when our apartment building suddenly began to shake around midnight on the 7th of September. I was annoyed because at first I thought the shaking was caused by someone on the floor below us playing music really loud.

But I quickly realized that I didn’t hear any music and that there were no pauses in the shaking like those that follow the melody of a song. That’s when I yelled to Cecilia, who was in the living room, “Es un temblor?” (It this an earthquake?) She yelled back to me “yes” in a voice that I remember noting did not seem worried or scared. However, after about 5 more seconds of continuous shaking, we started moving towards each other, with me putting on my flip flops and grabbing my phone and her grabbing her dog Bolita.

We met at the front door of our apartment. At this point the alarm system the city of San Cristóbal had just installed and tested not even two days before began sounding. With it, the shaking grew stronger and stronger. Huddled near the doorway (the strongest part of the apartment), we saw things start to fall off the bookshelf in the living room. I was already trying to turn on my phone’s flashlight when the lights went out.

Our apartment is on the second floor in a hallway that wraps around an inner courtyard, meaning the side of the hallway that faces the courtyard is made entirely of glass windows. So when we opened the front door and saw the windows that made up the other side of the hallway shaking a lot, that’s the moment I got scared. I don’t know why it took me that long to have an emotional reaction, but I think it was because every second that passed before that, I kept thinking the shaking would stop.

But it wasn’t stopping. De hecho, it was only getting stronger. Cecilia and I looked at the windows, looked at each other, and I could tell she was considering what we should do, but still did not seem freaked out. Suddenly we heard screaming down in the lobby of the apartment building, and Cecilia said we should go outside. At this point it had been temblando (shaking) for more than two minutes. So, we shut the door and started to make our way downstairs in the dark using the light of my phone. I kept looking up at the light fixtures, scared that they would fall on us, but thankfully by the time we reached the main entrance of the building, the shaking had stopped.

We walked out into the cold night air to find a lot of other people in the street. We spoke with some neighbors, making sure everyone was alright and accounted for. Suddenly, Cecilia turns to me and jokingly says, “¡Bienvenida a México!” (Welcome to México!) with fake enthusiasm. I busted out laughing in response, appreciating her attempt to lighten to mood, given that we were ok, everyone near us seemed ok, and our building didn’t seem to have suffered any damages. However, the laughter didn’t help my nerves. For about an hour after the shaking stopped, I found that my own body would not stop shaking uncontrollably – partly because of my nerves, partly because of the cold, and perhaps partly because of the actual shaking of the earthquake (who knows).

One thing that left an impression on me was that within a minute of walking outside, Cecilia knew (through social media) the magnitude of the earthquake (8.4 on the Richter scale) and the location of the epicenter (off the coast of Chiapas). In the minutes after receiving that information, Cecilia and other locals around me immediately began to send and receive thousands of messages via Whatsapp, the main messaging app used in Mexico, to friends and family around the country, making sure everyone was ok. Thankfully, everyone that I personally knew and everyone that those people personally knew were alright.

However, even as they confirmed this, the city’s alarm system continued sounding due to all of the aftershocks that were happening seemingly without end. We began to see and hear emergency vehicles, police vehicles, protección civil going toward el centro (the center) of the city. On Whatsapp, Cecilia and our neighbors were receiving tons of videos and pictures from places around the country that had felt the earthquake.

Cecilia told me that strong aftershocks were expected to occur between 3 am and 5 am. She wanted to stay outside until at least the alarm system stopped going off. However, it didn’t die down in frequency until around 2 am, and at that point we went back inside. Fortunately, I had barely felt any of the aftershocks, so I went to sleep, but with the light on initially (just in case another strong one happened and we had to evacuate the building again).

Gracias a Dios I and everyone I know was okay after the earthquake, but other people and buildings were not so fortunate. The next morning, we surveyed the damage to the old historic buildings in the center of San Cristóbal, which were roped off, and we learned that a mother and a daughter in another part of the city died when a wall of their house fell down on them.

We began to see the images from Oaxaca, where several houses and buildings collapsed, a fate shared by many small coastal communities of Chiapas.

In the following days, we learned that over 90 people across the country had died as a result of the earthquake and hundreds were injured. It was the strongest earthquake Mexico had experienced in a century, and it was going to take them a while to recover from it.

Given that I had just been caught by Hurricane Harvey in Houston during the week before I flew out to Mexico, I couldn’t believe that I was at the center of two historic natural disasters in two different countries in less than two weeks. Cecilia and I even joked that I must have offended Mother Nature because it seemed like she was out to get me.

And now, just yesterday, a second strong earthquake struck México (which was actually the combination of two earthquakes that happened milliseconds apart – a 6.8 quake centered in Puebla, México and a 7.1 earthquake centered in Morelos, México). Más encima, on the anniversary of Mexico’s massive 1985 earthquake that left more than 10,000 dead. On the day when survivors of the ‘85 quake were being interviewed about their experiences exactly 32 years ago. On the day when, just hours before, many parts of Mexico performed a simulacro (an earthquake drill). On the day when medical and rescue brigades from Mexico City had literally just stepped onto Oaxaca’s soil to help with recovery efforts–only to turn right around and go back to Mexico City, since they are needed more there right now.

***Thus, this is the most important part of this blog post***

Firstly, I want to steal a page from the blog of my friend Katie Becker, who is teaching English on a Fulbright grant right now in Ixtapan de la Sal, México, México:

“Take Climate Change Seriously and Elect Politicians Who Will Do The Same

It’s easy to see how rising global temperatures lead to stronger hurricanes, tornadoes, and typhoons. What may be less obvious is that climate change can also make earthquakes, tsunamis, and volcanoes more likely. Volcanologist Bill McGuire writes:

“Now, global average temperatures are shooting up again and are already more than one degree centigrade higher than during preindustrial times. It should come as no surprise that the solid Earth is starting to respond once more. In southern Alaska, which has in places lost a vertical kilometre of ice cover, the reduced load on the crust is already increasing the level of seismic activity.”

That should shake us to the core. Pun intended.”

Secondly, I want to tell you about a-little-talked-about phenomenon that I have learned about since arriving to Mexico nearly 3 weeks ago. Often when a natural disaster happens in Mexico, a single place stays circulating in the news/on social media and a lot of donations go to that place, leaving other places (most of them poor small towns that are isolated with no way to solicit help) whose situation is just as bad or worse, without the help they so badly need.

Thirdly, I want to emphasize that experts in natural disaster relief efforts agree that CASH is a much more effective form of aid than in-kind donations. Why? Because it is difficult to know exactly what is needed (and in what quantities) in each of the places that is affected by a tragedy. Donating cash avoids surpluses or shortages by allowing people and organizations on the ground to buy what people truly need and distribute it accordingly. Furthermore, often money is needed for things like the reconstruction of houses and buildings (which obviously cannot be donated in kind).

SO PLEASE REMEMBER:

- Chiapas and Oaxaca are not done with their recovery from the Sept. 7th quake – they very much still need contributions to their relief efforts.

- After the most recent Sept. 19th earthquake, images and video showing the damage and loss of life in Mexico City are the main ones circulating all over the news/social media. However, my Mexican friends who have lots of experience organizing relief efforts for tragedies like this assure me that Mexico City will have plenty of aid for its relief efforts (due to being the biggest city, the most visible as the capital, having the most organized infrastructure to respond to something like this, etc.) and that donations are much more needed in places like the Mexican states of Puebla and Morelos.

- If you live in the U.S., don’t worry there is a way you can still donate money! Here are a list of organizations that are accepting donations and are helping directly with earthquake relief efforts:

PLACES YOU CAN DONATE:

- UNICEF Mexico: https://www.donaunicef.org.mx/landing-terremoto/?utm_source=mpr_redes&utm_campaign=tw-terremoto&utm_medium=tw&utm_content=tw-org&utm_term=tw-org

- Mexican Red Cross: https://cruzrojadonaciones.org/

- Brigada de Rescate Topos (a local disaster relief organization): Donate through Paypal: donativos@brigada-rescate-topos.org

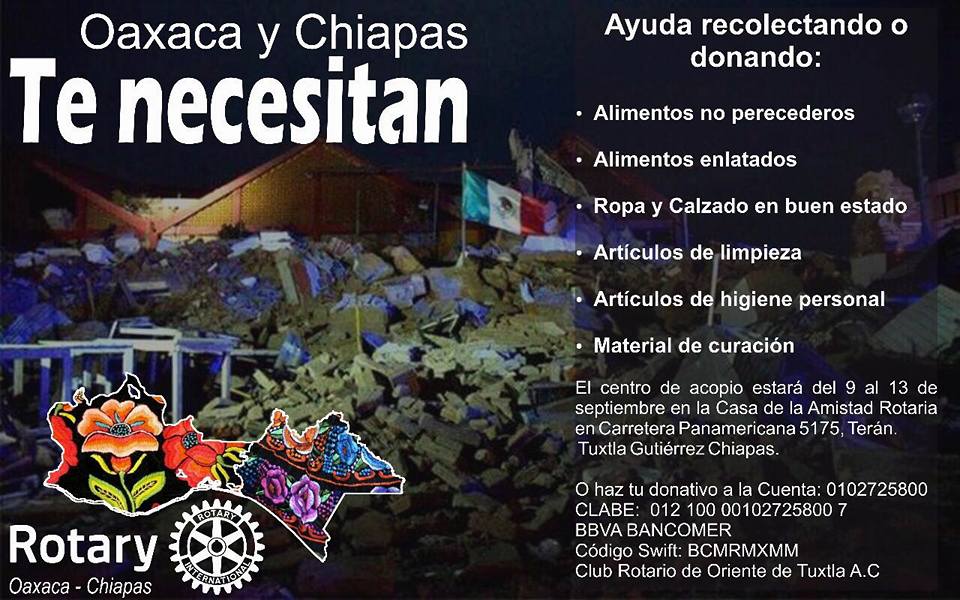

- Local Rotary Clubs in Oaxaca and Chiapas who are organizing funds for supplies, as well as the rebuilding of houses and buildings (one of whom is the Rotary Club that is hosting me during my stay here, so I can personally vouch for the trustworthiness of their work):

Bank Name: BBVA Bancomer

Bank Account Number: 0102725800

Key: 012 100 00102725800 7

Bank’s SWIFT/BIC Code: BCMRMXMM